Last week, I voraciously consumed a 2023 law review article published by María P. Angel and Ryan Calo criticizing Daniel Solove ’s Taxonomy of Privacy and Professor Solove’s 2024 critique of that paper and other criticisms. Solove’s Taxonomy has been highly influential and plays an enormous role in my work, from it uses in my book Strategic Privacy by Design, to its help in formulating privacy values underpinning my use of the NIST Privacy Framework, and finally as a model of normative consequences in privacy threat and risk modeling. Solove’s Taxonomy has been foundational in my work as a privacy engineer. I recall one of my interns once saying “but doesn’t every privacy professional know Solove’s Taxonomy?” to which I, disheartened, replied “No.” What follows is my, rather utilitarian, defense of the taxonomy.

As Solove describes in his response, Angel & Calo (2023) seek a sort of privacy essentialism, a way of framing and talking about privacy that creates clear boundaries between it and other fields. However, the concept of privacy mirrors the boundaries of privacy harms — fuzzy, mutable and with not only disagreement but differences owing to culture and subjectivity. I’ve always viewed privacy conceptually as a bubble separating the individual from society: the interior the province of the individual and the exterior the province of society. Historically, the bubble was your physical private space, separating you from the public space: your house, your thoughts, things with clear demarcation lines between inside (your house, your yard or your head). The modern bubble, though, metaphysically represents you, your tendrils into society, everything there is about your existence. Whether it be your physical presence, your information, your acquaintances, or your property, the bubble is, metaphorically, you. Some of us have small bubbles, some large. That bubble can be breached, but the bubble is also hazy. The boundary is a tug of war between individuals and society, “an actual [subjective] expectation of privacy … that society is prepared to recognize as ‘reasonable’” (Katz v. United States). Privacy is the study or attempt to define this boundary between you and not you, who is allowed in and who is not.

As the volleys between Solove and his detractors suggest, these boundary setting problems implicate many other social issues. This is where he and Angel & Calo diverge. They view privacy essentialism, as Solove terms it, as clear knowledge of the boundary line between privacy and not privacy. In other words, which boundary line we’re talking about should not be subject to debate. Rather, the debate, the province of the study of privacy, is where to draw the line. Note the conceptual difference between the line between privacy issues (e.g. confidentiality) and non-privacy issues (e.g. climate change) versus, within privacy, what should be held in private and not in private. Analogously, privacy essentialism says we know there is a geographic boundary between Russia and the Ukraine, but drawing that line is subject to fierce debate. Solove’s argument boils down to there being many different lines between political entities, and it’s not just where to put that boundary line that is debatable but whether that boundary falls under the umbrella of the term “privacy.” Furthering the analogy, what is the boundary between the United States federal government and individual states or even tribal nations. Now we’re not talking about geographic boundaries but jurisdictional ones. Solove, in his bottom-up taxonomy, aimed to identify “privacy problems that have achieved a significant degree of social recognition.” In other words, what boundaries are we even talking about in this umbrella term? This meta-boundary setting problem (what do we set as the boundaries up for discussion that we then need to set) is a fatal downfall of Solove’s Taxonomy, according to Angel & Calo. We can’t properly discuss privacy until we have a unified definition of privacy, they say, because Solove’s approach risks encroaching on too many other fields of analysis (such as consumer protection, discrimination, etc. though not climate change, which presumably most agree is not a privacy issue )

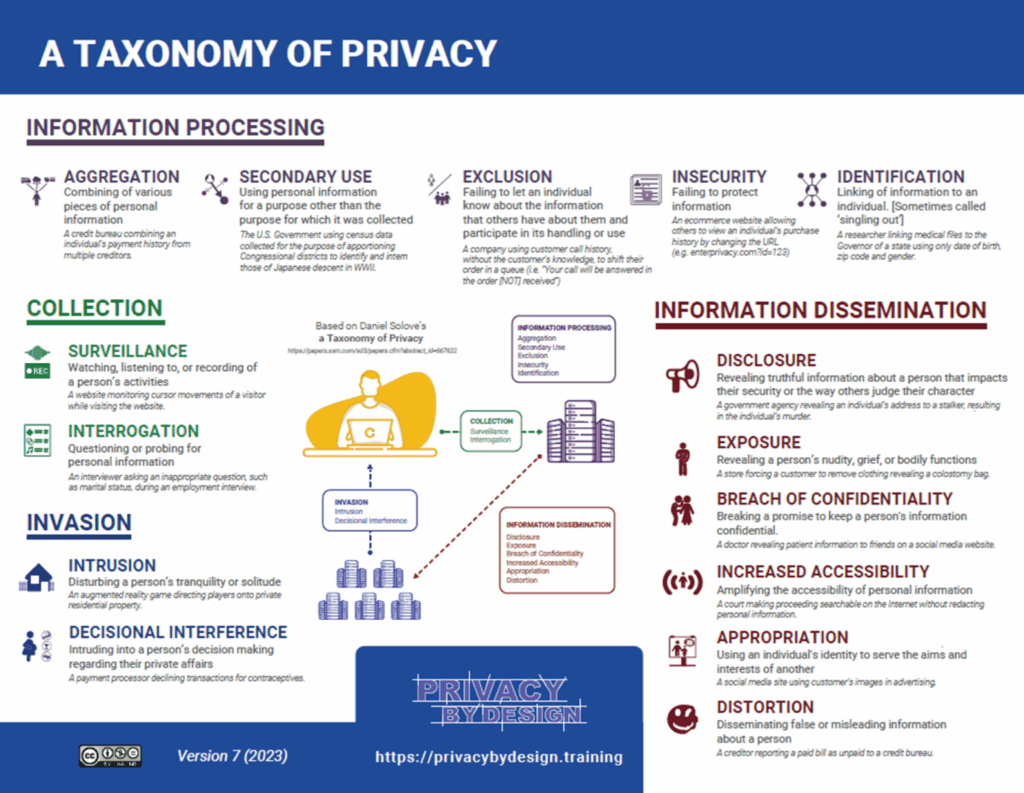

Engineers, though, are ever pragmatic. Talking about “privacy” is unhelpful in privacy engineering. I can’t translate a philosophical construct into actions. Solove’s Taxonomy helps break this ambiguous lofty term into discrete digestible activities that can be identified and acted upon. Telling an engineer to solve privacy is about as useful as telling them to solve health. They need something more concrete (solve an arrhythmic heart). Telling them that it may be problematic when data is collected over time or from multiple sources (potentially the harm of aggregation, under the taxonomy), now they can start developing a solution. Once the potential aggregation points are identified, engineers can build in controls: minimize data coming into the system (less data, less data to aggregate), obfuscate the data (making it harder to combine into profiles of individuals), or get informed authorization from individuals and through the “magic of consent” turn a harm into a service (“click this button and we’ll gather up all references to you on the web and write your profile for you!”).

Angel & Calo’s criticism of social recognition of privacy harms, though, is spot on in one regard. When does the combining of data sources reach the threshold of the harm of “aggregation?” Who decides that the aggregation of data, something that information rich companies do persistently, is even a normative harm (i.e. violates social norms)? Who is the authority designating this a “harm?” This is something that I struggle with in my consulting business with clients. In training, I can give copious examples of where society expresses disgust for aggregation, using, as Solove did, in his original paper, “historical, philosophical, political, sociological, and legal sources.” I can cite Alan Westin’s opinion piece in the New York Times in March 1970:

“Retail Credit [Corporation’s] files may include ‘facts, statistics, inaccuracies and rumors’ … about virtually every phase of a person’s life; his marital troubles, jobs, school history, childhood, sex life, and political activities.”….“Almost inevitably, transferring information from a manual file to a computer triggers a threat to civil liberties, to privacy, to a man’s very humanity because access is so simple.”

Now known as Equifax, Retail Credit Corporation’s creation of vast dossiers on Americans and the social disdain of their practices, led to the passage of the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA), one of the earliest consumer privacy laws. Upon learning this, many people are shocked. The day to day operations of privacy programs obfuscates this rich history of why we have privacy programs and privacy laws. The need to support these discussions on the social norms of privacy and its history led me to create the volunteer driven Privacy Wiki, a site dedicated to cataloging hundreds of news stories of “privacy problems” organized, of course, by…. drum roll please… the Solove Taxonomy.

What I’ve ultimately settled on though is that it is the clients’ prerogative as to what harms they are willing to recognize. Many focus on the information processing and dissemination harms, owing to the outsized influence of data protection laws. More recently, a recognition that the manipulative interfaces and deceptive designs call for deeper introspection of points of “decisional interference” in consumer engagements. But, ultimately, they decide what they are going to address. This is part of the reason the Institute of Operational Privacy Design’s (IOPD) Design Process Standard calls for organizations to adopt and specify their own risk model. It’s a very real realization that no organization, currently, is going to address every privacy harm. It’s a matter of prioritization and risk management. Frankly, it’s a win if organizations even define their risk model, which few do. Similarly, in the IOPD’s forthcoming standard for products and services, while the Institute is more prescriptive about the risk model, organizations applying the standard can still selectively specify which risks are in scope and which not, again owing to the realization that prioritization will inevitably leave some harms out of consideration.

Angel & Calo’s further criticism of the taxonomic approach addresses the lack of resolution between privacy-privacy conflicts. Another point I’ve seen play out first hand. How do you prioritize two competing claims? This is no easy problem to solve and, in fact, the IOPD’s subcommittee on Privacy by Default struggled to come up with an answer. When the configurability of a system only impacts one issue for one person, the default configuration is a no brainer. The default should be the less harmful, less risky option. But what happens when flipping a switch decreases one privacy harm only to increase another? What if turning on caller-id exposes the caller’s phone number but allows the recipient to avoid unwanted intrusions? Should the default be the caller-id is suppressed to protect the confidentiality of the caller but now the recipient is unable to avoid undesired calls? You may fall on one side or the other, but hopefully you’ll admit there is an argument to be made from both perspectives. Angel & Calo argue that a unified theory of privacy would help resolve these conundrums, but I see no evidence to support that. Ultimately, the IOPD decided, for their forthcoming standard, that rather than try to resolve this broadly and generically in the standard, applicants will need to construct an argument as to why they choose the default they did and back that up by evidence such as surveys showing nobody cares about caller confidentiality and everyone hates intrusive callers.

Ultimately, I find Solove’s Taxonomy useful in practice. In a sea of talks about addressing “privacy issues,” solving “privacy problems,” improving “privacy,” reducing “privacy risk,” the taxonomy can provide a grounding in more specific, more concrete activities that can be examined and addressed, in practice.

[The author is president of the Institute of Operational Privacy Design, which is leading the way in creating practical and thoughtful leadership in the privacy engineering space. Our forthcoming standard on privacy by design and default will be available in draft months before being open for public comment. To get you or your company involved, consider joining. Lifetime membership is only available through year end.]

This post has been cross posted on https://privacymaverick.com